Step by Step to a virtual process twin

New opportunities for a more precise analysis and design of value networks

1 Areas of application for digital twins

2 Set uo a digital twin for a process: that's how it's done

3 New options for evaulating controlling and qualifying suppliers

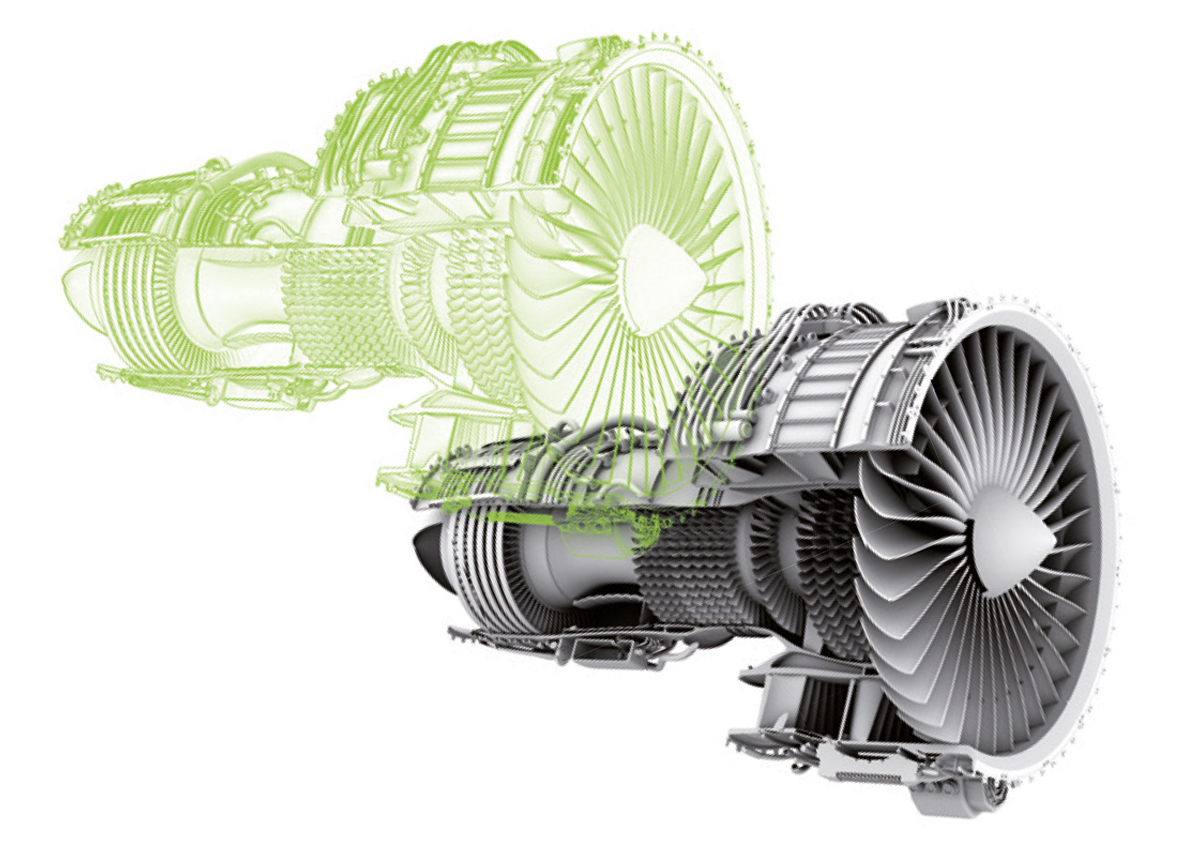

Digital twins, i.e. virtual models that mirror their physical counterparts extremely closely and in real time, are among the particularly impressive examples of Industry 4.0 and the Internet of Things. The transformative role of this approach will most certainly take on even greater significance in the next few years as it gains universal acceptance. Until then, there is still a long way to go. If we take a look at where digital twins – at least those that actually deserve the name – are deployed, we will see that they are used in particular in the fi eld of highly complex capital goods: wind generators and turbines, power station components, and special machinery. It is here that the effort associated with developing a digital twin is worthwhile, and it is here that it is possible to collect suffi cient operating and status data in order to design a valid mirror image. And it is here that a digital twin offers real added value.

For example, if you can develop a digital twin for an aircraft turbine – something which is very expensive, critical and durable – you can, ideally, very accurately predict when material fatigue or operational deterioration will occur, when the turbine needs preventive maintenance, and what environmental factors are particularly critical. This naturally saves a great deal of money, as nothing costs more than an aircraft in a hangar. And furthermore, you can also generally learn where the weak points in the design are and draw important conclusions from this for future production.

So far, so good – exciting and very promising. And yet this interpretation of a digital twin still falls short of the mark because, while the approach described above defi nitely supplies valuable lessons regarding the optimization of a product and its maintenance, you only gain real optimization leverage when not just the product but also the entire process – or even the entire value network – is improved. It is only when digital twins are established for processes and not just for products that the full potential of digitalization and interlinking can be leveraged.

The starting point for this is the definition of process parameters that might possibly influence the performance of the production line

Incresed efficiency and quality are the obvious benefits that can be achieved with the "digital process twin" - but not the only ones by a long shot.

What does the development of a digital twin for a process involve?

Let’s take the example of a production line for dashboards in the automotive industry that processes – i.e. molds and hardens – polyurethane foam. It frequently suffers from a relatively low level of effi ciency and high reject rate, especially in the light of very high standards in the industry. The problem here is not located at the product level, but at the process level. A digital twin will now be developed to improve this process.

The starting point for this is the defi nition of process parameters that might possibly influence the performance of the production line. These values are derived from experience and might initially comprise far in excess of one hundred different parameters, which may increase or decrease during further analysis.

The second step involves ensuring that existing process data are correctly aggregated and configured, that data which can be captured but have so far not been registered are collected, or that data which have not yet been captured but are required in the light of the defi ned parameters are then measured using additional sensors. The data pool that is generated in this way is then merged and analyzed in a cloud application. This gives rise to a model that maps the process being optimized as accurately as possible: the relevant parameters, their interdependencies, and critical values. One particularly interesting aspect here is that this model can reach out far beyond the company in question – like the process itself. In this example, it may also extend to the logistics service provider that transports the foam, or even to manufacturer of the foam itself, because the causes of the problem, such as dangerous temperature fl uctuations in the highly reactive polyurethane, can arise at any point in the value chain. The result is a digital copy of the process that can monitor the entire physical process in real time, allowing for early intervention based on critical process parameters – a “digital process twin”.

Increased efficiency and quality

are the obvious benefi ts that can be achieved with the “digital process twin” – but not the only ones by a long shot. The approach thus opens up new possibilities for evaluating, managing and qualifying suppliers, since using virtual process models makes it possible to analyze the actual structures and processes in the value chain much more accurately and thoroughly than with the checklists and lean manuals that are customary today. First, this provides a very good lever for qualifying suppliers. Second, it allows new partners to be integrated far more rapidly and easily, reducing dependencies and facilitating the establishment of new, local production facilities. This also makes virtual process twins a major strategic factor in developing smart supply chain management.